Unless there is some major political development, Brexit takes place on 29 March 2019 and, at present, there is to be an implementation or transition period lasting until the end of 2020.

The paper is lengthy (104 pages) and lacks elegance. "Cakeism" is a word used by some to describe the government's "cake and eat it" approach to Brexit and here we see a half-baked cake riddled with serious problems.

The government "red lines" were set as far back as the Prime Minister's Lancaster House Speech in February 2017. The red lines appear to have been set entirely by Mrs May and include taking the UK out of the EU Single Market (SM) and Customs Union (CU) but the White Paper seeks a relationship containing features of the SM and CU.

Undoubtedly, many of the proposals will fail to meet with the EU's agreement and that makes a "No Deal Brexit" far more likely. A messy divorce with on-going rancour. The document may have been just about adequate as a starting point for the opening of Article 50 negotiations back in June 2017 but it is far from adequate at the present stage with just a few months left to secure agreement.

Nonetheless, it is worth remembering that, as long as the Conservative government is in place, this Policy Paper is the only plan on the table. At long last there is at least a basis for negotiation about the future relationship. Failure to achieve a Withdrawal Agreement will have immensely adverse consequences for the UK economy and maybe for the future of the UK as a "union."

It is to be noted that the government has stepped up its planning for a No Deal situation - e.g. The Guardian 9 July.

Document Overview:

After Forewords by the Prime Minister (pages 1 and 2) and the Secretary of State for Exiting the EU (page 3) there is an Executive summary (page 6). Four Chapters follow: [1] Economic partnership; [2] Security partnership; [3] Cross-cutting and other co-operation; [4] Institutional arrangements. Finally the Conclusion and Next Steps are set out. This post notes those conclusions and then looks at the proposed Institutional Arrangements. A further post will look at [1], [2] and [3].

Conclusions and Next Steps:

The aim is to finalise the Withdrawal Agreement and the Framework for the Future Relationship by October 2018. The two form a package. The European Parliament must give its consent to the conclusion of the Withdrawal Agreement.

The finalised documents will be debated in both Houses of the UK Parliament and, if the House of Commons supports a resolution to approve the Withdrawal Agreement and Framework, there will then be a Withdrawal Agreement and Implementation Bill to give the Withdrawal Agreement legal effect in the UK.

The White Paper recognises that the EU is only able legally to conclude agreements giving effect to the future relationship once the UK has left the EU in March 2019. It is proposed that the Withdrawal Agreement contains an explicit commitment by both parties to finalise these legal agreements as soon as possible in accordance with the parameters set out in the Future Framework. That would achieve a smooth transition out of the implementation period and into the future relationship.

Institutional Arrangements:

Chapter 4 proposes various institutional arrangements aimed at ensuring that there is a broad range of co-operation between the UK and the EU. The arrangements will reflect that the UK will no longer be a member of the EU and the EU institutions will no longer have power to make laws for the UK. The principles of direct effect and of the supremacy of EU law will no longer apply in the UK.

The UK's proposed institutional arrangements seek to enable new forms of dialogue to develop (para 4.3) and provide for flexibility as events unfold. The proposed institutional structure draws on arrangements made in other areas such as the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA).

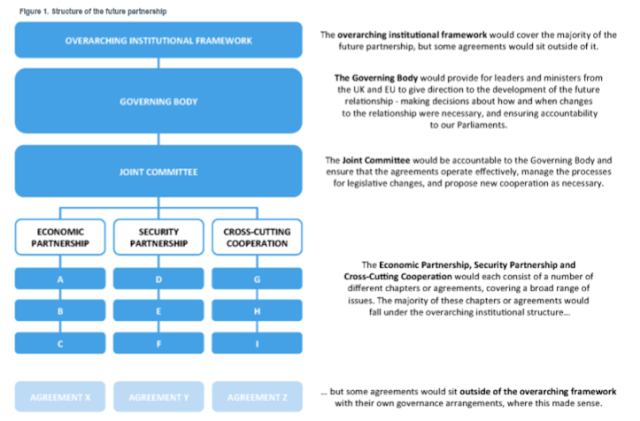

There would be an Overarching Institutional Framework. Within this Framework there would be a Governing Body to set political direction (para 4.3.1) and a Joint Committee (para 4.3.2) to provide technical and administrative functions.

This diagram shows the basic scheme -

Regular and formal dialogue between the UK Parliament and the European Parliament would be established. - (para 4.3.3).

In areas where the UK commits to a Common Rulebook (ongoing harmonisation of rules) it is proposed to have a mechanism for consultation over legislative changes. The UK would not have a vote on such changes but should be consulted on the same basis as member states. The White Paper sets out (paras 4.3.4 and 4.6) the arrangements for this. Obviously, the aim here is to address, at least in part, the criticism that the UK would become just a "rule-taker." The proposed consultation process seems likely to be unhappy given the economic might of the EU compared to the UK. This is certainly not a partnership of equals.

To ensure that the future relationship is administered effectively, the UK and the EU would need to agree arrangements for regulatory cooperation - (para 4.4). The arrangements would seek to ensure that (a) there is technical dialogue in the Joint Committee to oversee the application of legislative and regulatory commitments; (b) where there is a common rulebook that there is consistent interpretation; (c) there are arrangements for UK participation in EU bodies and agencies where this is required for the agreed cooperation to take place. Point (c) is addressed more fully in para 4.4.3 where it is said that the nature and structure of UK participation will vary depending on the EU body or agency in question. Whatever the level of participation agreed, the UK would have nowhere near as much influence as it currently enjoys as a full and long-standing EU Member State.

A considerable amount is said about the process for dealing with proposals for legislation (rule changes) - (para 4.4.1). If an agreement is updated to reflect a rule change then that would become a binding obligation on both parties in international law. The UK Parliament would be able to refuse to implement a rule change in domestic law and, if it did so, this could breach the UK's international obligation and the EU could then raise a dispute and ultimately impose non-compliance measures. It is hardly rocket science to see the potential for problems here in the event that the UK and the EU get to loggerheads over some issue.

The White Paper accepts that there is a need for consistent interpretation of the agreements in the UK and the EU. Such consistency is the prime raison d'être for the Court of Justice of the EU. Under the proposals, when courts in either the UK or the EU interpret legislation intended to give effect to the agreements, they could take into account the relevant case law of the courts of the other party - (para 4.4.2). References to the CJEU will not be possible once the UK has left the EU but it is said that this would not affect the consistent interpretation of a common rulebook. An element of wishful thinking there!

Dispute resolution is the subject of para 4.5. The aim is to resolve disputes by discussion. There would be an option for either party to refer the issue to an independent arbitration panel but what if the dispute is over interpretation of a common rulebook? Here the proposal is that there should be an option to refer the disputed point to the CJEU. Having obtained the court's interpretation, the Joint Committee or the arbitration panel would have to resolve the dispute in a way that was consistent with that interpretation. This proposed process would be separate to other routes the parties may have for resolving disputes in international agreements.

What if there is non-compliance? The proposal (para 4.5.2) is that the complaining party should be able to take measures to mitigate any harm caused by the breach. Measures would have to be proportionate to the scale of the breach, temporary and localised to the area of the future relationship that the dispute concerned. The type of measures could include financial penalties or suspension of specific obligations. Financial compensation is included in 11 free trade agreements including US-Australia etc.

A further paragraph (4.5.3) is headed Safeguarding against Shocks. There may be times when the unexpected happens and the parties have to act quickly. The agreement should provide for temporary action to be taken. If the action resulted in one party gaining an undue competitive advantage, the other party would have the right to take steps to rebalance the agreement. Any measures would be subject to challenge through independent arbitration.

A final section (4.6) deals with Accountability at Home. The agreements between the UK and the EU would require domestic legislation to give them effect in the UK. Where any legislative proposal relates to ongoing cooperation, the UK Parliament would have a role in overseeing and scrutinising it. In areas where the UK had committed to maintain a common rulebook with the EU, the UK Parliament would (a) be notified of the proposed change; (b) Parliament could express an opinion as to whether the proposed change was within the scope of the agreements; (c) the Joint Committee would decide whether to add a rule change to the relevant agreement and Parliament would be consulted about this; (d) Parliament would scrutinise legislative proposals and could decide not to enact the legislation but this would be in the knowledge that there would be consequences from breaking the UK's international obligations.

Where proposed rule changes were within the competencies of the devolved legislatures then the UK government would work with them to shape the UK's position ahead of discussions in the Joint Committee.

The paper states that "A similar process would take place in relation to areas where the UK and the EU had agreed that there was equivalence between respective rules." Equivalence is a problematic creature since a time could come when the EU decides that equivalence has to end and that the same rule has to apply with the same interpretation. Equivalence is explained by the Institute of Government HERE.

Finally, there is this ...

The Institutional Framework will be of crucial importance regardless of the arrangements in the Withdrawal Agreement. The White Paper proposes to give enormous authority to the "Governing Body" and vast influence to the "Joint Committee." Arbitration to resolve disputes is by no means unusual but the Court of Justice of the EU will still bind the EU in the event that an arbitration refers a point to the court. Further, the court's ruling would have to be acted upon by the UK if breach of international obligation was to be avoided.

It will be necessary for the powers of the Governing Body and the Joint Committee to be carefully defined. Clarity will be required as to the relationship between those bodies and the institutions of the EU and also the UK Parliament.

.

The greater problems lie within Chapters 1 to 3 and it is to those that we must now turn.

Announcement of the White Paper:

The UK's proposed institutional arrangements seek to enable new forms of dialogue to develop (para 4.3) and provide for flexibility as events unfold. The proposed institutional structure draws on arrangements made in other areas such as the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA).

There would be an Overarching Institutional Framework. Within this Framework there would be a Governing Body to set political direction (para 4.3.1) and a Joint Committee (para 4.3.2) to provide technical and administrative functions.

This diagram shows the basic scheme -

Regular and formal dialogue between the UK Parliament and the European Parliament would be established. - (para 4.3.3).

In areas where the UK commits to a Common Rulebook (ongoing harmonisation of rules) it is proposed to have a mechanism for consultation over legislative changes. The UK would not have a vote on such changes but should be consulted on the same basis as member states. The White Paper sets out (paras 4.3.4 and 4.6) the arrangements for this. Obviously, the aim here is to address, at least in part, the criticism that the UK would become just a "rule-taker." The proposed consultation process seems likely to be unhappy given the economic might of the EU compared to the UK. This is certainly not a partnership of equals.

To ensure that the future relationship is administered effectively, the UK and the EU would need to agree arrangements for regulatory cooperation - (para 4.4). The arrangements would seek to ensure that (a) there is technical dialogue in the Joint Committee to oversee the application of legislative and regulatory commitments; (b) where there is a common rulebook that there is consistent interpretation; (c) there are arrangements for UK participation in EU bodies and agencies where this is required for the agreed cooperation to take place. Point (c) is addressed more fully in para 4.4.3 where it is said that the nature and structure of UK participation will vary depending on the EU body or agency in question. Whatever the level of participation agreed, the UK would have nowhere near as much influence as it currently enjoys as a full and long-standing EU Member State.

A considerable amount is said about the process for dealing with proposals for legislation (rule changes) - (para 4.4.1). If an agreement is updated to reflect a rule change then that would become a binding obligation on both parties in international law. The UK Parliament would be able to refuse to implement a rule change in domestic law and, if it did so, this could breach the UK's international obligation and the EU could then raise a dispute and ultimately impose non-compliance measures. It is hardly rocket science to see the potential for problems here in the event that the UK and the EU get to loggerheads over some issue.

The White Paper accepts that there is a need for consistent interpretation of the agreements in the UK and the EU. Such consistency is the prime raison d'être for the Court of Justice of the EU. Under the proposals, when courts in either the UK or the EU interpret legislation intended to give effect to the agreements, they could take into account the relevant case law of the courts of the other party - (para 4.4.2). References to the CJEU will not be possible once the UK has left the EU but it is said that this would not affect the consistent interpretation of a common rulebook. An element of wishful thinking there!

Dispute resolution is the subject of para 4.5. The aim is to resolve disputes by discussion. There would be an option for either party to refer the issue to an independent arbitration panel but what if the dispute is over interpretation of a common rulebook? Here the proposal is that there should be an option to refer the disputed point to the CJEU. Having obtained the court's interpretation, the Joint Committee or the arbitration panel would have to resolve the dispute in a way that was consistent with that interpretation. This proposed process would be separate to other routes the parties may have for resolving disputes in international agreements.

What if there is non-compliance? The proposal (para 4.5.2) is that the complaining party should be able to take measures to mitigate any harm caused by the breach. Measures would have to be proportionate to the scale of the breach, temporary and localised to the area of the future relationship that the dispute concerned. The type of measures could include financial penalties or suspension of specific obligations. Financial compensation is included in 11 free trade agreements including US-Australia etc.

A further paragraph (4.5.3) is headed Safeguarding against Shocks. There may be times when the unexpected happens and the parties have to act quickly. The agreement should provide for temporary action to be taken. If the action resulted in one party gaining an undue competitive advantage, the other party would have the right to take steps to rebalance the agreement. Any measures would be subject to challenge through independent arbitration.

A final section (4.6) deals with Accountability at Home. The agreements between the UK and the EU would require domestic legislation to give them effect in the UK. Where any legislative proposal relates to ongoing cooperation, the UK Parliament would have a role in overseeing and scrutinising it. In areas where the UK had committed to maintain a common rulebook with the EU, the UK Parliament would (a) be notified of the proposed change; (b) Parliament could express an opinion as to whether the proposed change was within the scope of the agreements; (c) the Joint Committee would decide whether to add a rule change to the relevant agreement and Parliament would be consulted about this; (d) Parliament would scrutinise legislative proposals and could decide not to enact the legislation but this would be in the knowledge that there would be consequences from breaking the UK's international obligations.

Where proposed rule changes were within the competencies of the devolved legislatures then the UK government would work with them to shape the UK's position ahead of discussions in the Joint Committee.

The paper states that "A similar process would take place in relation to areas where the UK and the EU had agreed that there was equivalence between respective rules." Equivalence is a problematic creature since a time could come when the EU decides that equivalence has to end and that the same rule has to apply with the same interpretation. Equivalence is explained by the Institute of Government HERE.

Finally, there is this ...

The Institutional Framework will be of crucial importance regardless of the arrangements in the Withdrawal Agreement. The White Paper proposes to give enormous authority to the "Governing Body" and vast influence to the "Joint Committee." Arbitration to resolve disputes is by no means unusual but the Court of Justice of the EU will still bind the EU in the event that an arbitration refers a point to the court. Further, the court's ruling would have to be acted upon by the UK if breach of international obligation was to be avoided.

It will be necessary for the powers of the Governing Body and the Joint Committee to be carefully defined. Clarity will be required as to the relationship between those bodies and the institutions of the EU and also the UK Parliament.

.

The greater problems lie within Chapters 1 to 3 and it is to those that we must now turn.

Announcement of the White Paper:

We’ve published our White Paper. Setting out how we will secure the best #DealForBritain— Exiting the EU Dept (@DExEUgov) July 12, 2018

📝 https://t.co/lswqH1zcgw pic.twitter.com/h9CBO4kzpM

No comments:

Post a Comment